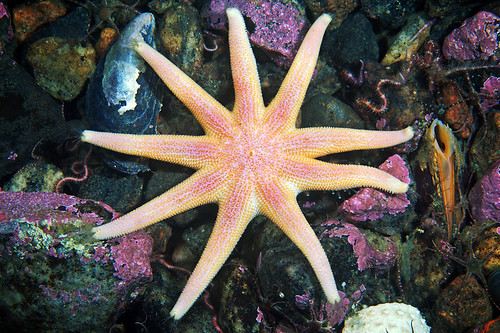

Members of the Asterinidae include some 150 species in over 25 genera spread out all across the world. Everywhere from the deep-sea to under rocks in the tropical Atlantic and Pacific. Most have five rays, whereas others, such as Meridiastra calcar from Australia can have up to 8 or 9..

The many species go by several familiar common names: Bat star, cushion star, Knitted star..

This is actually a good place to identify the very distinctive patterns in asterinids.. namely, these crescent or "knitted" looking plate patterns on the body surface..

In fact, the Japanese word for sea star.. hitode, which means palm, may actually be BASED on an asterinid (Patiria pectinifera).But for once, there's quite a lot known about them! So here's five subjectively interesting facts about them!

1. They live everywhere

Asterinids occur all over the world with many in shallow water habitats, including under rocks in places as diverse as the North Atlantic. They often live under rocks, or hidden away in cryptic habitats..

There is a HUGE diversity of these tiny little guys. Some are able to reproduce asexually but others just seem to get around.. Being small and easily transported...

to tropical habitats in Singapore...

But honestly, one of the places you are MOST likely to encounter them is here.. in a tropical reef aquarium. These tiny ones are most likely in the genus Meridiastra or Aquilonastra.

But honestly, one of the places you are MOST likely to encounter them is here.. in a tropical reef aquarium. These tiny ones are most likely in the genus Meridiastra or Aquilonastra.Again, this is one of those species which is small and easily transported.. Living rock is a GREAT place for them to turn up..

This aquarium species is asexual and once one gets into your aquarium, you're most likely going to have a bunch of them after too long...

So, you can encounter shallow water asterinids almost all over the world! Australia, South Africa, South America, Antarctica, North America, etc, etc.

But as with most starfish groups, there are often weird deep-sea members... Both of these get to be pretty big sized animals.

I've mentioned these briefly before.. the flat one on the left is called Anseropoda, which is SO flat that it feels like a cloth rag when you pick it up! We know very little about it.. Sometimes, small ones are so thin that light shines through them! Its name literally means Ansero for "goose" and "poda" for foot.. So, Goosefoot starfish! These can get to be almost 1.5 feet across!

The one on the right, is called Tremaster mirabilis. Katie Gale and her colleagues found that these will feed on coral in the North Atlantic. As a species it occurs widely around the world including the North Atlantic, the South Pacific and near Antarctica.

Asterinids practically EMBODY the classic feeding mode of stomach eversion in sea stars! Here's a classic video I've been showing since the blog started! It shows the stomach extended out onto the glass and feeding on the algae and other good stuff. Most other asterindis feed in a similar fashion...

One of these days, somebody needs to actually make a video of this thing feeding!

|

| This image from SeaFriends in New Zealand |

3. Reproduction! Lots of it! Asterinids are one of the most heavily studied sea stars because of their many reproductive strategies...

Some, such as this "Asterina panceri"(Asterina gibbosa) actually BROOD their young

|

| From Byrne 1996, Fig. 4h |

and I've reported in the past on this other brooding species, which live inside their mother and whose babies will actually EAT one ANOTHER!

And of course when all else fails, there's always dividing yourself! Asexual or fissiparous reproduction is why those tiny aquarium stars are so numerous!

3. Commensal Worms! In the Pacific Northwest species, Patiria miniata, its been know for quite some time that there's actually a species of polychaete worm (Ophiodromus pugettensis) that actually lives on the underside!!

This is one of the better studied species of asterinids, but there's many other species of Patiria and other species such as Patiriella and Meridiastra which have a similar surface morphology and are conceivably "habitats" for other animals...

4. They are important to the Evolution of Sea Stars!

A few years ago, I and my colleague Dave Foltz published this DNA tree of one of the most diverse clusters of the Asteroidea- the Valvatacea, which included several members of the Asterinidae.

Here's figure 2 from our paper...

Yeah, I know the image is hard to read, but basically, what I wanted to show was how the Asterinidae seems to show close relations with several other groups of sea stars, including the big multi-armed predators, the Solasteridae

and the enigmatic Antarctic Perknaster..

and of course, there's more I haven't summarized here.. their phylogentic history relative to their various interesting features, etc.. but that's another post!

![Asteroidia | Asterinidae | Patiriella calcar [Variegated Sea Star] - Flat Rock, Ballina, NSW](https://c1.staticflickr.com/9/8605/15718261567_bf8e2295d1_k.jpg)