|

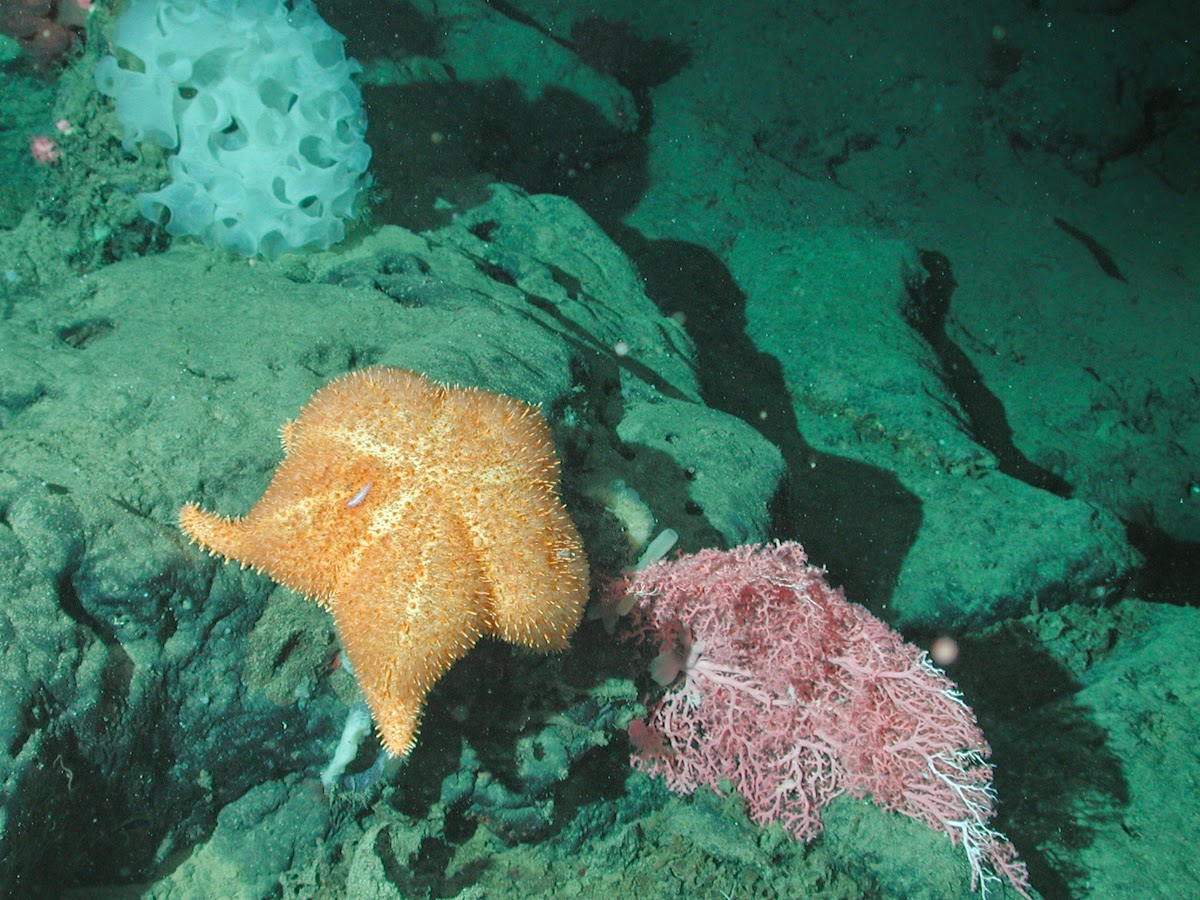

| Image from STRI's O. reticulatus page |

The species name "reticulatus" refers to the net-like pattern on the body surface whereas "Oreas- refers to "mountain"... So breaking it down, the latin name means "Reticulated Mountain Star."

O. reticulatus is a pretty iconic animal for this region. It is so, distinguished that it even occurs on the 1 cent coin on the Common Wealth of the Bahamas!!

These have been made into CUFFLINKS!

and postage stamps!

The genus Oreaster only in the tropical Atlantic, on both the east and west side and is known only to occur in shallow water. Oreaster reticulatus tends to be thought of as being primarily a west Atlantic species.

The east Atlantic/African species of Oreaster is called Oreaster clavatus and varies in color and spination...

|

| Image borrowed from this excellent French site for identifying marine fauna "Sous les Mers" |

Moving on! Adults do vary somewhat in color (note also juveniles below)... Some lighter

Some darker...

Most times, these are 5 rayed, but occasionally you get the odd one with 4 or 6..

But enough with the intro!! Here we go!

5. Oreaster reticulatus are omnivorous feeders but eat a lot of algae and encrusting food. Often, they feed in feeding "fronts"

So, one of the seemingly constant assumptions (I would say misconceptions) that are often made of sea stars is that they ALL adhere to the feeding modes of shallow-water asteriids, such as Asterias.. i.e., the old trope of "all starfish feed on mussels or clams" I have written at length about the diversity of feeding modes in sea stars. You can see more of that here. and here..

O. reticulatus feeds primarily on microalgae and/or on other kinds of encrusting food. Work by Scheibling (1980 in Marine Ecology Progress Series 2: 321-327) shows them feeding on a seagrass bed where they obtain nutrients from a likely combination of organisms on the seagrass, the seagrass, and organic materials in the sediment, etc. but what's interesting? is HOW they do this...

When Oreaster reticulatus feed, they do so in a FEEDING FRONT!! Kind of like an army across the sand bed...

The pic below hails from the paper cited. The authors describe this feeding front:

A feeding front of the sea star Oreaster reticulatus off St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands. The front is moving from left to right. Feeding mounds (fm) of darker sediment surrounded by lighter halos can be seen behind the front on the highly turbated sand bottom. In advance of the front, the sediment appears darker because of a microalgal film which has developed in the absence of sea star grazing in the previous weeks. Average sea star diameter is 0.26 mMaybe their effect is similar to that of some sea cucumbers?

Also worth noting? Food varies with location. Some feed on algae, but others feed on sponges. In some places, up to 61% of the species were feeding on MANY different sponge species (see Wulff 1995 in Marine Biology 123: 313-325)

Even MORE interesting? Feeding by O. reticulatus is so specific that they can actually tell apart different species of sponges that humans cannot recognize! (see Wulff 2006 in Biol. Bulletin 211: 83-94)

3. Juveniles are a different color/appearance than the adults.

Oreaster reticulatus are members of the family Oreasteridae. As adults, these are big, massive very heavily armored individuals. But when smaller, most have a VERY different looking juvenile form.

This, for example, is a photo of the many growth forms that the Indo-Pacific Cushion star, Culctia novaeguineae undergoes as it gets bigger.

The same is true for Oreaster reticulatus, which undergoes size AND color transformations as it increases in size.... This probably varies even MORE depending on where the animal lives, and what its food might be...

This one is more grey/brown...

3. O. reticulatus "home in" on large aggregations of other O. reticulatus

|

| Image from Echino LifeDesks. Photo by Simon Coppard |

They performed an experiment, where a big bunch of individuals present on a large sand patch were moved off the patch to about 20 m (about 66 feet) into the surrounding seagrass bed.

As the internet is fond of saying "What happened next, WILL AMAZE YOU!" (or at least, I thought it was interesting...) the starfish then, re-oriented and then moved BACK to the patch, re-grouped with the others within 24 hours! That is, they HOMED in on the OTHER starfish and MOVED there.

How? Probably through some kind of chemosensory cue in the water. i.e., something that those starfish leave behind that informs the others how to find them. So, yes, they can tell where they are and determine where others are as well.

2. O. reticulatus is closely related to another species in the East Pacific!

One of the cool things about many of the animals which are found in the tropical Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico, is that you can often look toward the East Pacific (i.e. the other side of the Panamanian isthmus) and find ANOTHER species which often bears a close resemblance!

I wrote a story awhile back about a starfish species, Heliaster kubiniji, found as a living from in the East Pacific, but ALSO as an extinct, fossil form from Florida.

Long story short? About 10 million years ago the isthmus of Panama was not yet closed. And it was an open waterway between the "Gulf of Mexico" and the eastern Pacific (south of Baja California).

There were MANY species in this area were once connected. Some were one continuous species while others just kind of showed a close genetic connection. Then the isthmus formed about 3-5 million years ago and formed a barrier, separating these two populations.

Before we had better genetics and fossils to tell us about the precise timing, these were often assumed to be "sister" species. In other words, two sides of the same coin.. closely related by only a few million years of separation. But it is now clear to us that several of these diverged from one another much earlier than that. And are thus much more distantly related than was previously thought...

1. O. reticulatus faces "predation pressure" from tourists and studies on populations and reproductive biology do not suggest it will do well if overfished.

Yeah, sorry, this one is not quite as fun or neat as the others, but its important. I've written about the pending threat of "overfishing" starfish species in the Indo-Pacific. This includes the widely occurring Protoreaster nodosus as well as several other fished species (Archaster, etc.)..

In the tropical Atlantic, O. reticulatus is regularly taken as fodder for tourist shops and so forth. The pressure on this industry has become significant and in many places the populations of this species have become locally extinct.

Based on work by Scheibling & Metaxas (see this and MANY other refs) the population of this species are relatively low, ranging from 1 to 5 individuals per 100 sq. meter and don't turn over very quickly. It is unclear how much growth goes into a large sized, adult individual, but it doesn't seem that these are very fast growers.

The species is dependent on the algae and other food found on seagrass beds, which suggests that between collection of the adults and habtiat destruction or disruption, this does not bode well for the big familiar "cushion stars" of the tropical Atlantic..

So, here is a species that seemingly everyone takes for granted but if it has an ecologically important role, maybe one we haven't fully understood? and we're taking it for tourist baubles and souvenirs??

Something to think about...

....and one extra! .. I'll be honest and say I'm not sure if this is pooping...or spawning..

.jpg)